Valuing uncertainty and curiosity in politics

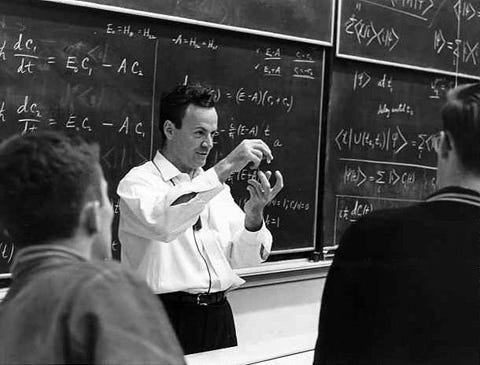

Lessons for politics from physicist Richard Feynman

In 1963, Nobel prize winning physicist Richard Feynman gave a series of three lectures, the second of which was entitled “This Unscientific Age.” His argument holds equally true today:

“Suppose two politicians are running for president, and one goes through the farm section and is asked, ‘What are you going to do about the farm question?’ And he knows right away – bang, bang, bang. Now he goes to the next campaigner who comes through. ‘What are you going to do about the farm problem?’ ‘Well, I don’t know. I used to be a general, and I don’t know anything about farming. But it seems to me it must be a very difficult problem, because for twelve, fifteen, twenty years people have been struggling with it, and people say that they know how to solve the farm problem. And it must be a hard problem. So the way that I intend to solve the farm problem is to gather around me a lot of people who know something about it, to look at all the experience that we have had with this problem before, to take a certain amount of time at it, and then to come to some conclusion in a reasonable way about it. Now, I can’t tell you ahead of time what conclusion, but I can give you some of the principles I’ll try to use - not to make things difficult for individual farmers, if there are any special problems we will have to have some way to take care of them,’ etc. etc.

Now such a man would never get anywhere in this country, I think. It’s never been tried, anyway.”

What is expected of politicians to win elections is the same thing that is perpetrating our distrust not only in politicians, but in government and in science more broadly. Feynman articulated the problem well in 1963, and it remains the same — if not worse — today. The demand from the population for a clear answer on every issue perpetuates the position of politicians who pretend to know everything. But the politician is not able to keep all of their promises. As a result, nobody believes the politician’s promises. And the result of that is a disillusionment in politics more generally and a lack of respect for people who are trying to solve problems.

I am by no means saying all politicians are bad people. But it feels clear to me that the system needs to change. We need people in leadership positions to be able to say “I don’t know,” and have a process that instead leverages our collective wisdom and enables us to solve problems in new ways.

In January, I co-facilitated a prototype Student Assembly at MIT about the principles that should govern use of generative AI. The task of students and faculty at the university over the course of three full days was to learn about the issue and to develop a set of recommendations that needed at least 75% support amongst the group to be adopted. One of the Assembly Members shared with me afterwards one of the reasons why it was such a powerful experience for them. He came from an organising and advocacy background, where he was expected to come into spaces with certainty and conviction for his views in order to succeed in winning over others. He realised that it was a shift for him to be welcomed into a space where everyone was invited to say “I don’t know,” to learn together, to ask questions together, to identify gaps in knowledge and understanding needed to move forward in developing collective solutions.

When it comes to public decisions that affect a community, it’s why discussion and deliberation is crucial. In his lectures, Feynman also made a compelling argument for why scientific and moral arguments are independent of one another. Science helps us to understand what is likely to happen if we do something. Collective deliberation helps us to decide whether we want that to happen. In politics, we need to consider both. Yet our current institutions and processes centred around election campaigns, political party logic, and charismatic leadership do not incentivise public decision making that is grounded in both scientific evidence and discussion of collective values.

There has been a breakdown in trust in science and in information quality, as well as a lack of spaces for deliberation (distinct to dialogue and debate). Deliberation meaning a collective weighing of evidence with the goal of reaching a shared decision. Dominant forces have pulled in two directions - populism on the one hand and technocracy on the other. Together they have hollowed out the space for identifying collective values and have undermined trust in science and scientists.

Information and arguments are being dismissed merely because of who is making the argument rather than as the basis of the argument itself. This is equally the case in academic institutions. The free speech debates happening across campuses are also related to this trend. People feeling like they are unable to voice certain perspectives because they fear that someone might complain (formally or informally) about feeling ‘unsafe’ or offended. (See Jeannie Suk Gerson’s New Yorker article about this).

It feels more crucial than ever to invest in the creation of spaces and processes that help to ignite curiosity, enable genuine listening, and welcome respectful disagreement. We will never all agree entirely about everything. It’s not possible, and I would argue that it’s not desirable either.

With that being the case, we need these deliberative spaces in our political institutions - as well as other institutions of daily life like universities and colleges, schools, workplaces, associations, and others. Spaces where people can spend time together, over lengthier periods of time. There is no magic shortcut to solving the deep trust problems underpinning the breakdown of social cohesion, the growing polarisation, and people’s sense of alienation and lack of belonging. Technology can’t fix them for us, and we can’t skip them either.

It’s why I defend the value of longer-form deliberative processes and spaces like Citizens’ Assemblies that typically last 4-6 days, often longer, over many months. Sometimes people ask if there are lighter-touch ways — like whether a day or two, or doing the process online — would create similar effects and outcomes. It depends on your goal. If you want to strengthen trust in a lasting way, this takes time. If you want people to be able to feel more open and vulnerable, to be willing to get into the hard conversations respectfully, and to come up with genuinely thoughtful and ambitious propositions that don’t shy away from the complexities and trade-offs of an issue, and carry legitimacy for implementation, then the short answer is no.

Would you trust the recommendations of a group deliberating on the intricacies of legislation surrounding a contentious issue like abortion after just a day of deliberation? In Ireland, the Citizens’ Assembly on abortion met over the course of five months. They made detailed proposals for how legislation should change if the Irish public voted for changing the constitution on the issue. The French Assembly on End of Life deliberated for 27 days over 9 weekends. They reached 92% consensus on 67 recommendations, written up in a 176 page report delivered to President Macron and considered by a parliamentary committee.

The weight and legitimacy is of another scale than if either of these Assemblies had convened for a shorter period of time. Not to mention that it would not have been possible to go into the sometimes difficult and emotional conversations.

While it is technically possible to do things entirely online, it is neither easier nor cheaper as is often the reasoning for doing so. It also begs the question of what problem is one trying to solve by doing that? It’s much harder to do the trust- and group-building work that enables the safety for having hard group conversations and is necessary for helping people to grapple better with complexity. Especially when that group is extremely diverse — I’m referencing examples where people were selected by sortition (by lottery) to be broadly representative of society.

In Ireland and France, Assembly members shared pints in the pub and drinks over World Cup matches in between deliberations. These social moments amongst people who would normally never cross paths, coming from different parts of the country, with different life experiences, educational experiences, and perspectives (much more heterogeneous than our governing class) are part of the essential ingredients for success in strengthening trust and creating the conditions that better enable people to handle the complexity of an issue.

During this mega-election year, we will hear many politicians argue with certainty about their solutions to the problems we face. I hope more journalists give a spotlight to those who are recognising that they don’t and never will have all the answers. That part of the solution is about changing our political processes and institutions to create deliberative spaces like Citizens’ Assemblies as essential parts of an expanded democratic architecture.

More Citizens’ Assemblies are happening in more places around the world. Imagine if they were anchored in as permanent institutions like our parliaments and city councils, with real power, in cities, regions, and countries across the globe - like in Paris, Ostbelgien, and Brussels. The fact that this is already happening and more politicians and citizens alike are creating and demanding this change gives me hope that another democratic future is possible.

This piece was first published on the DemocracyNext newsletter.

Hi Claudia! Loved loved loved this piece... the value of leaders being able to say "I don't know"... this is something that has started to happen more and more in the realm of progressive business... it's key that it can happen in the realm of progressive government, as well. And here's to investing in the "creation of spaces and processes that help to ignite curiosity, enable genuine listening, and welcome respectful disagreement."

Speaking of "respectful disagreement"... back in the day, scientists used to believe that tv sets had to be a certain minimum size, as they were based on a certain kind of tube. Then technology changed, and all of a sudden we had mini-TV's that had been deemed "impossible" before... I fully agree with you, that time is a significant ingredient... no magic wands here... AND YET, sometimes advanced technology looks a bit like magic. Here's a link to a case study that shows, how much can be done in a single long weekend... when we have the "social technology" that enables us to do so: https://www.co-intelligence.institute/case-study-macleans